------------------------------------------------------------------------

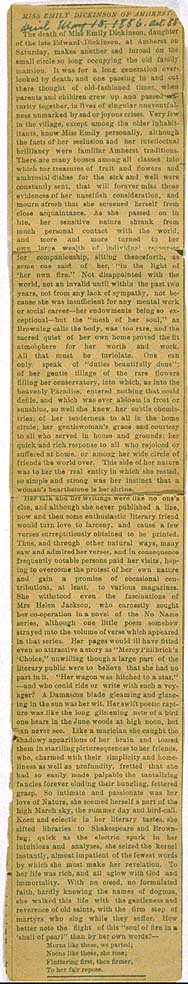

Miss Emily Dickinson of Amherst.

[in ink; appears to be Susan's handwriting:

Died May 15, 1886. age 55]

The death of Miss Emily Dickinson, daughter

of the late Edward Dickinson, at Amherst

on Saturday, makes another sad inroad on the

small circle so long occupying the old family

mansion. It was for a long generation over-

looked by death, and one passing in and out

there thought of old-fashioned times, when

parents and children grew up and passed ma-

turity together, in lives of singular uneventful-

ness unmarked by sad or joyous crises. Very few

in the village, excepting among the older inhabit-

itants, knew Miss Emily personally, although

the facts of her seclusion and her intellectual

brilliancy were familiar Amherst traditions.

There are many houses among all classes into

which her treasures of fruit and flowers and

ambrosial dishes for the sick and well were

constantly sent, that will forever miss those

evidences of her unselfish consideration, and

mourn afresh that she screened herself from

close acquaintance. As she passed on in

life, her sensitive nature shrank from

much personal contact with the world,

and more and more turned to her

own large wealth of individual resources

for companionship, sitting thenceforth, as

some one said of her, "In the light of

'her own fire." Not disappointed with the

world, not an invalid until within the past two

years, not from any lack of sympathy, not be-

cause she was insufficient of any mental work

or social career-- her endowments being so ex-

ceptional--but the "mesh of her soul," as

Browning calls the body, was too rare, and the

sacred quiet of her own home proved the fit

atmosphere for her worth and work.

All that must be inviolate. One can

only speak of "duties beautifully done";

of her gentle tillage of the rare flowers

filling her conservatory, into which, as into the

heavenly Paradise, entered nothing that could

defile, and which was ever abloom in frost or

sunshine, so well she knew her subtle chemis-

tries; of her tenderness to all in the home

circle; her gentlewoman's grace and courtesy

to all who served in house and grounds; her

quick and rich response to all who rejoiced or

suffered at home, or among her wide circle of

friends the world over. This side of her nature

was to her the real entity in which she rested,

so simple and strong was her instinct that a

woman's hearthstone is her shrine.

Her talk and her writings were like no one's

else, and although she never published a line,

now and then some enthusiastic literary friend

would turn love to larceny, and cause a few

verses surreptitiously obtained to be printed.

Thus, and through other natural ways, many

saw and admired her verses, and in consequence

frequently notable presons paid her visits, hop-

ing to overcome the protest of her own nature

and gain a promise of occasional con-

tributions, at least, to various magazines.

She withstood even the fascinations of

Mrs. Helen Jackson, who earnestly sought

her co-operation in a novel of the No-Name

series, although one little poem somehow

strayed into the volume of verse which appeared

in that series. Her pages would ill have fitted

even so attractive a story as 'Mercy Philbrick's

'Choice," unwilling though a large part of the

literary public were to believe that she had no

part in it. "Her wagon was hitched to a star,"

--and who could ride or write with such a voy-

ager? A Damascus blade gleaming and glanc-

ing in the sun was her wit. Her swift poetic rapt-

ure was like the long glistening note of a bird

one hears in the June woods at high noon, but

can never see. Like a magician she caught the

shadowy apparitions of her brain and tossed

them in startling picturesqueness to her friends,

who, charmed with their simplicity and home-

liness as well as profundity, fretted that she

had so easily made palpable the tantalizing

fancies forever eluding their bungling, fettered

grasp. So intimate and passionate a part of the

high march sky, the summer day and bird-call.

Keen and eclectic in her literary tastes, she

sifted libraries to Shakespeare and Brown-

ing; quick as the electric spark in her'

intuitions and analyses, she seized the kernel

instantly, almost impatient of the fewest words

by which she must make her revelation. To

her life was rich, and all aglow with God and

immortality. With no creed, no formulated

faith, hardly knowing the names of dogmas,

she walked this life with the gentleness and

reverence of old saints, with the firm step of

martyrs who sing while they suffer. How

better note the flight of this "soul of fire in a

shell of pearl" than by her own words? -

Morns like these, we parted;

Noons like these, she rose;

Fluttering first, then firmer,

To her fair repose.